Early Days Of Pre-Compton And Environs

The origins to Compton Bassett and its surrounding region stretch back almost 10,000 years, following the end of the last ice age. As the climate became warmer humans began to move in to the region. The earliest finds of human activity are flint tools from the Mesolithic period (c.8,000–4,000 BC), indicating post-glacial activity of people hunting and gathering across the region. It was a largely nomadic existence based on the movement of grazing animals and fruit gathering.The occurrence of flint for tool-making in chalklands such as ours made this a resource-rich place in which to be, so the downs immediately south and east became a hotbed of activity as time went on. And unlike other parts of Britain, the landscape of the Wiltshire downs was dominated by open grassland and only punctuated by outcrops of woodland. Into the Neolithic (c.4,000–2,500 BC), the practice of cultivation and animal husbandry began to take hold and there was a move towards a more sedentary life, as the idea of land division and constructing earthworks and monuments was initiated (eg West Kennet Long Barrow, Windmill Hill, Avebury, Silbury Hill). Windmill Hill, 2½ miles east, is the largest and one of the oldest known examples of a causewayed enclosure (initial phase 3,800 BC), which is an earthwork made up of concentric rings of ditches with frequent breaks, or causeways. Its purpose seems to have been as a meeting place for large gatherings of people; numerous cattle and sheep bones found excavated from the ditch fill suggest that it could have been an important place for ceremonial meetings or feasting. A settlement in the Compton Bassett areapossibly existed in one form or another from about these times.

Early Bronze Age pottery and worked flint were discovered from test pits dug near Compton Farm in a research project carried out in 1994; this offers the first clear indication of occupation. Other evidence through the Bronze Age (c.2,500–800 BC) comes from the circular burial mounds that pepper the landscape, of which we have six in the parish. The nearest is in Mount Wood and is a fine specimen at over 3 metres high and around 15 metres in diameter; it is so high and conical shaped, that it has been suggested it could concievably be a later, and rare, Romano-British example.

There is also evidence of late Bronze Age (c.1,000 BC) activity on the top of Cherhill Down, when the first digging of banks and ditches to enclose a 6 hectare site was carried out. Some 500 years later, the enclosure was developed further, extending the earlier work to 9 hectares and creating more elaborate ramparts along the boundary, as well as many internal features of pits and probably round houses. Today, we know this site as Oldbury Castle Hillfort. It is the nearest Iron Age (800 BC – AD 100) presence to the village, that can be seen today. Roman occupation left traces within the parish, such as pottery fragments in the scarp face at Roach Wood and a probable pottery kiln near Manor Farm. The remains of early medieval watermills and fishponds lie about 500 metres south-east of Freeth farm and were mentioned in Domesday Book (AD 1086). The original mill was most likely used for grinding corn and was converted to a fulling mill probably between the 14th and 16th centuries.

The Three Domesday Estates

The early communes that would evolve and later become Compton Bassett appear to have developed from two spring-line settlements. The first originated at the mouth of a coombe where the church and present main house lie. A second settlement with the buildings of Compton Cumberwell manor stood at the mouth of another coombe half a mile north-east. A third estate recorded in Domesday looks to have merged with Compton Bassett manor early in the 13th century, and may have existed near Freeth Farm.

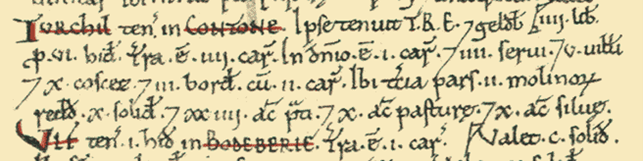

From around the 9th century AD the settlement of Compton [Bassett] was in the hundred of Calne. As was the case under the feudal system the king was the only true ‘owner’ of land in England. In Domesday Book Contone (possibly King’s Land), is given as the latinised version for the origin to modern Compton Bassett. Following the Norman invasion, Domesday Book recorded Compton [Bassett] as three estates totalling 17½ hides, an assessment chiefly based on land quality rather than actual area and used for taxation. It is estimated to have had sufficient arable land for 12 plough teams, together with 68 acres of meadow, 30 acres of pasture and 30 acres of woodland. The population was said to be 53 households (possibly around 190 to 220 people), putting it in the top 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday. Consequently, Compton was obliged to provide three fully armed soldiers for service to the king. Domesday records the names of a tenant-in-chief, or overlord, who ‘held’ the land on behalf of the king.

Compton Estate

Standing at the mouth of a coombe, along which runs the track commonly referred to as Hooper’s Lane, was Compton Cumberwell manor (also Comberwell, Comerwell). This third estate also comprised 6 hides. Andrews & Drury’s map of 1773 places the name ‘Compton Comerwell or Comberwell’ across the middle area of the present village, roughly from White’s farm to Compton Hill. Cumberwell is probably derived from cumb, Old English for a short valley, ‘by a stream or spring’.

This was held by Thurkil (or Turchil) de Arden (c.1040–1100) and, unusually for an Anglo Saxon, was still in his possession in 1086. At about this time two water mills were shared equally between those holding the three estates at Compton Bassett in 1086 and could well have been the two mills known to belong to the lord of Compton Bassett manor in 1228. In the late 1100s an exchange of lands took place between Alan Basset and Hugh de Cumberwell, the lords of both manors.

Late in the 12th century or early 13th century William of Cumberwell held the manor. In 1222, it was held by his son Hugh; in 1242–3 Hugh’s son Philip de Cumerwell; and in 1289 by Philip’s son Sir John. In the 13th century Compton Cumberwell manor consisted of demesne (estate) and customary holdings. The overlordship of Compton Cumberwell had become part of the barony of Castle Combe, as Walter de Dunstanville was overlord in 1242–3.

Compton Cumberwell is frequently confused with another Cumberwell (Cumbrewelle), a manor near Bradford on Avon. This is not helped by the fact that, after the Norman Conquest, Humphrey De L’Isle was the overlord of both estates.

The Cumberwell family dropped out by 1327, when a Roger de Berlegh became the holder, followed by his son, Roger junior. Fishponds are recorded in 1342, belonging to the lord of Compton Comberwell and are described as likely to have been on the clay in Compton Bassett (probably in joint ownership with Compton Bassett manor).

Meetings of a court for Compton Cumberwell manor are recorded for 10 years between 1405 and 1444 and for 11 years between 1548 and 1571. Although most business was tenurial, the homage presented defaulters and those who neglected to repair buildings or scour ditches.

Between 1405 and 1530 it was held by the Blount family or their married relations. One of these, John Hussey, sold the manor to Sir William Button and from then on it passed in direct line for five generations. In the later 16th century four copyholders (tenure of parcels of land) of Compton Cumberwell manor held between them 39 acres of arable, 7 acres in closes of meadow and pasture, and grazing rights for 9 cattle, 4 horses, and 80 sheep. Land holdings for the manors were generally increasing from around this time through enclosure, the controversial removal of common land into private ownership.

In 1660 the estate passed from another Sir William to his brother and, through his wife Eleanor, to second brother Sir John Button. At the start of the 18th century Compton Cumberwell manor land was still in four holdings. When Button died in 1712, there being no direct line, grandnephew Heneage Walker inherited and when he died in 1758, his brother John Walker acquired Compton Cumberwell. In the same year he bought Compton Bassett house with the parkland and ten years later his son John bought the rest of Compton Bassett estate and merged the two manors.

The manor of Compton Comberwell was still referred to as such on 25 July 1807 when a newspaper notice was published from Compton House to warn people from trespassing and poaching on their lands (which included Compton Basset, Cherrill, Lyneham and Preston).

Late and Post-Medieval Estates And Farms

More recent estates are recorded within the northern area of the present village. One was held by John Blake in the late 15th century. The main house for Blake’s estate is not known but it is likely to have developed into Manor Farm, which was built in 1691. At that time the Maundrell family were in possession and continued for several generations until the early 19th century. By 1831 it was acquired by George Walker-Heneage.

In 1719 Michael Smith bought two dwellings and 120 acres of land on the northern outskirts of the village. The old houses were later demolished and his son, Michael Jnr, set about building a new house for which the foundation stone was laid in 1737. This house would later be called Dugdale’s. Smith was married to Margaret Sharpe, a young widow and heiress who hailed from Compton Bassett herself. It passed through the Smith family for two generations and then, in 1780, went to a niece and her husband, Richard Dugdale. When Richard’s grandson sold it in 1855 to George Walker-Heneage, it was then 350 acres. The main house with gardens, outbuildings and adjacent fields amounted to 42 acres. The other part was Lower End Farm which totalled 273 acres.

Streete Farm, mainly an 18th century building with an earlier back wing from the 17th century, and Austin’s Farm opposite (18th century), are in close proximity to each other along with Manor Farm. This group was referred to as Silver Street in the 1773 edition of Andrews and Dury’s map. Silver Street is a common place name for which there are several possible definitions; a more likely one is that it is a corruption from the latin silva, which means a wood. Because of the latin connection, it has often been found to be associated with Roman origins. It is also conceivable that it is a corruption of Selewyn’s Street, recorded in the 13th century.

The Village Post 1950's

It was not until 1953 that mains electricity became widely available in Compton Bassett and mains water would not be installed until the 1960s. Of the seven separate farms: Freeth, Home, White’s, Compton, Manor, Dugdales and Lower End, all except Freeth were dairies. But before the century was out, this had whittled down to just one, at Manor farm. The village school closed in March 1964 as numbers of children attending had been steadily declining since the war.

Sources

Blackford, J.H. 1941. The Manor and Village of Cherhill. Private Publication.

Crowley, D.A. (ed.) 2002. A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 17. London:

Victoria County History.

Reynolds, A.J. 1994. Compton Bassett and Yatesbury, North Wiltshire: settlement morphology and locational change. Papers from Institute of Archaeology 5.

Stephen, L. and Lee, S. (eds). 1885–1900. Dictionary of National Biography.

Volumes I–63. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

with thanks to Mr Laurie Waite

Compton Bassett Village.

The Old Stable

Street Farm, Compton Bassett

SN11 8SW

Phone: +44 1249 760597

Email: info@comptonbassett.org.uk